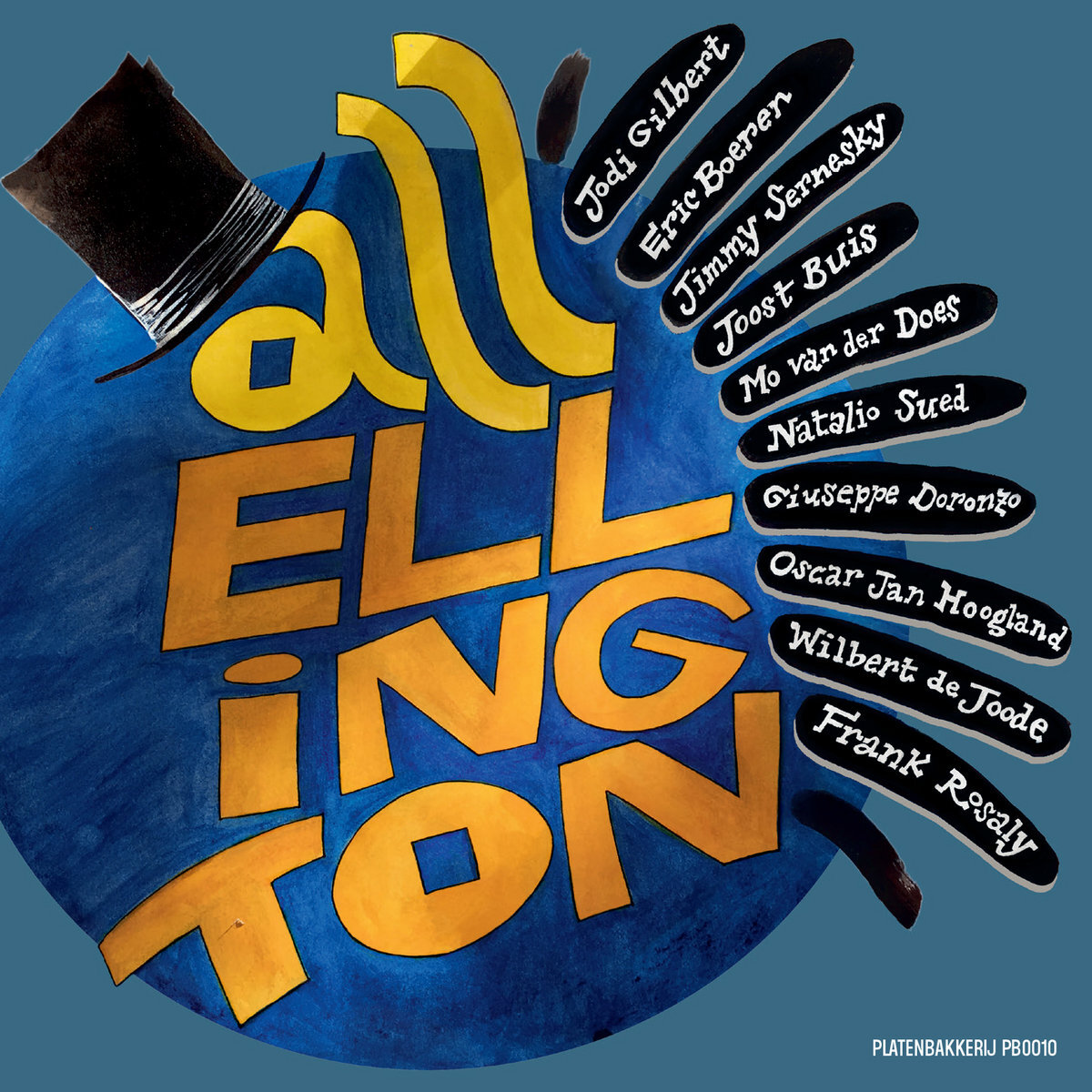

pbakk010: All Ellington: All Ellington

Jodi Gilbert voice

Mo van der Does alto sax, clarinet

Natalio Sued tenor sax/clarinet

Giuseppe Doronzo baritone sax/bass clarinet

Eric Boeren cornet

Jimmy Sernesky trumpet

Joost Buis trombone

Oscar Jan Hoogland piano

Wilbert de Joode bass

Frank Rosaly drums

Jodi Gilbert voice

Mo van der Does alto sax, clarinet

Natalio Sued tenor sax/clarinet

Giuseppe Doronzo baritone sax/bass clarinet

Eric Boeren cornet

Jimmy Sernesky trumpet

Joost Buis trombone

Oscar Jan Hoogland piano

Wilbert de Joode bass

Frank Rosaly drums

Jodi Gilbert voice

Mo van der Does alto sax, clarinet

Natalio Sued tenor sax/clarinet

Giuseppe Doronzo baritone sax/bass clarinet

Eric Boeren cornet

Jimmy Sernesky trumpet

Joost Buis trombone

Oscar Jan Hoogland piano

Wilbert de Joode bass

Frank Rosaly drums

TRACK LISTING

1. Night Song

2. Strange Feeling

3. Sonnet for Sister Kate

4. (In My) Solitude

5. Zweet Zhursday

6. Black and Tan Fantasy

7. Sophisticated Lady

8. Lament for Javanette

9. Sonnet in Search of a Moor

10. Mount Harissa

REVIEW

The intergenerational Amsterdam collective

All Ellington, started by Eric Boeren, has been playing music by Duke,

Strayhorn and company since 2013. Its ranks also include A’dam improvising

linchpins Joost Buis, Wilbert de Joode and Oscar Jan Hoogland, so you might

reasonably infer they play the compositions with respect and also slide out of

the frame into freer space, sometimes improvising transitions between pieces.

Misha Mengelberg’s/ICP’s engagement with the Ellington repertoire 30 years

ago set that template. But after five years of breaking down the original charts

by ear, and honing them in intensive rehearsals (Boeren: “We have several

band members with a terrific ear for harmony”) and despite some personnel

changes, All Ellington also do something trickier. As their eponymous CD

demonstrates, they frequently animate the elusive Ellington effect itself, the

sound of Duke’s actual scoring, working with only three reeds and three brass.

Not just the totemic pixie-mutes-under-plungers wah-wah stuff, but the

sublime Strayhorn reed voicings. Putting all of that together, they make this

music their own.

Cornetist Boeren, and the other principal arranger, trombonist Buis, first

played obscure Ellington in the early 1990s, before they ran their respective

Ornette and Sun Ra repertory projects, bands that slid into and out of the

sounds of their role models the way All Ellington does, and which had Wilbert

de Joode on bass. The under-performed Ellington here come from various

suites, Perfume to Far East, and from Barney Bigard and Cootie Williams small

groups. There are also some evergreens.

To achieve that Ellington effect, it helps that altoist Mo van der Does (20 when

the band recorded) and baritone saxist Giuseppe Doronzo can slide into

Johnny Hodges inflections and Harry Carney vibrato at will, but use those

powers sparingly. Tenor Natalio Sued, given the Paul Gonsalves slot on "Mount

Harissa” only meets Paul halfway, retaining his own Argentine romantic (and

Warne Marsh-loving) side. (The saxophonists double on clarinets/bass

clarinet.) In a similar way, Buis may reference Juan Tizol or the Joe Nanton yaya

lineage (notably on “Sonnet for Sister Kate”, Boeren’s chart with organ

chords from background horns).

The effect also relies on idiosyncratic blending of the horns—AE’s pocket-sized

sections are tight—and that deft arranging: ex-bandmember Michael Moore's

setting of “Mount Harissa” with its five-voice backgrounds for Sued’s steaming

catch the flavor of the original, or Buis’s “Zweet Zurzday” refining the 2003

version by his Astronotes.

The brass trio reunites Boeren and trumpeter Jimmy Sernesky, for the first

time since Available Jelly’s gem Monuments (Ramboy) 25 years earlier.

Sernesky is a terrific, too little known sweet/tart lyrical player who gets good

exposure here, notably on the opener “Night Song”, a jaunty Tizol/Jimmy

Mundy ballad Cootie recorded in 1937. AE’s version starts with a stark

repeating saxophone bell/block chord like an oncoming night train and which

carries on, persistently, till the reeds slide into silky Duke mode midway

through. Boeren opens up “Black and Tan Fantasy” to give Sernesky more

room to strut, and does a little plunger Bubbering of his own. Eric also steps up

on the collectives, where, per Dutch practice, dynamics and density are

conscientiously varied, and relations are in flux.

On three pieces singer Jodi Gilbert joins the nonet. She is typically heard in

abstract and sometimes broadly expressive settings—try Spoon 3’s Seductive

Sabotage (Evil Rabbit)—and mixes it up with the horns, in particular on

Boeren’'s broadly growly “Strange Feeling.” (But then here come those

saxophones again.) She sings “Sophisticated Lady” and “Solitude” disarmingly

straight, with sweetness (early on at least), the way Duke preferred ballads

sung. She lays out the word “sol-i-tude” with even note values on the first two

syllables, just as Ellington wrote it, where other singers tend to shorten that

short i, swinging the word like a triplet. That small choice speaks to how

closely they all mind the original texts, before heading for the hills.

Wilbert de Joode’s plump bass attack is as valuable here as everywhere else,

and period appropriate. He’s their Blanton, and it’s good to hear him romp

through changes. He gets the melody statement on “Sonnet in Search of a

Moor”, under clarinet pastels, and nudges the bow along on the intro to

”Sophisticated Lady”, arranged by Doronzo who channels Carney aping Hodges.

Ex-Los Angeles, ex-Chicago drummer Frank Rosaly applies his Billy Higgins

training. Sometimes understatement is more effective, not least where so

much is happening already. Rosaly doesn’t play like this is a big band. He

keeps things swinging with a light touch.

It’s a tall order, being the pianist in an Ellington tribute band. Oscar Jan

Hoogland handles it very deftly, evoking Duke’s decorations on “Sophisticated

Lady” and getting at the jabbing drive on “Mount Harissa" without neglecting

his own investigations of piano timbre: his strummed autoharping under the

hood on “Zweet Zurzday”, say. Hoogland just hints at a reggae lope on “Sonnet

in Search of a Moor”—more than a whisper would be too much. (Precedent:

the Mercer Ellington ghost band’s ghastly “Queenie Pie Reggae.”) On “Harissa”

or “Black and Tan”, Hoogland blows up the Ellington percussive gestures

beyond life size. The pianist does much to set the tone, in an unobvious way,

exemplifying the band’s approach: Duke’s music is too pretty not to play

straight, but we also do this other weird stuff (that we can also trace back to

him). They know that if you’re going to play the genius music, you can’t dumb

it down. —Kevin Whitehead, Point of Departure